From Malahide Castle to Vicar Street: What Live Music Has Taught Me About My New Life in Ireland

DUBLIN, IRELAND (February 13, 2026) — Since I moved from the United States to Ireland on July 4, 2023 (yes, Independence Day), I’ve made it a point to take in as much live music as possible.

Since arriving, I’ve found myself in crowds across Ireland — and occasionally beyond — watching artists whose careers span decades. Some nights were in sprawling outdoor settings like Malahide Castle or Marley Park. Other nights were inside the cavernous 3Arena. Sometimes I was in the intimacy of the Olympia Theatre or Vicar Street, or outdoors at Iveagh Gardens, or seated at the National Concert Hall.

Dublin’s live music scene is deep and varied. And over the past two and a half years, I’ve seen it from nearly every scale.

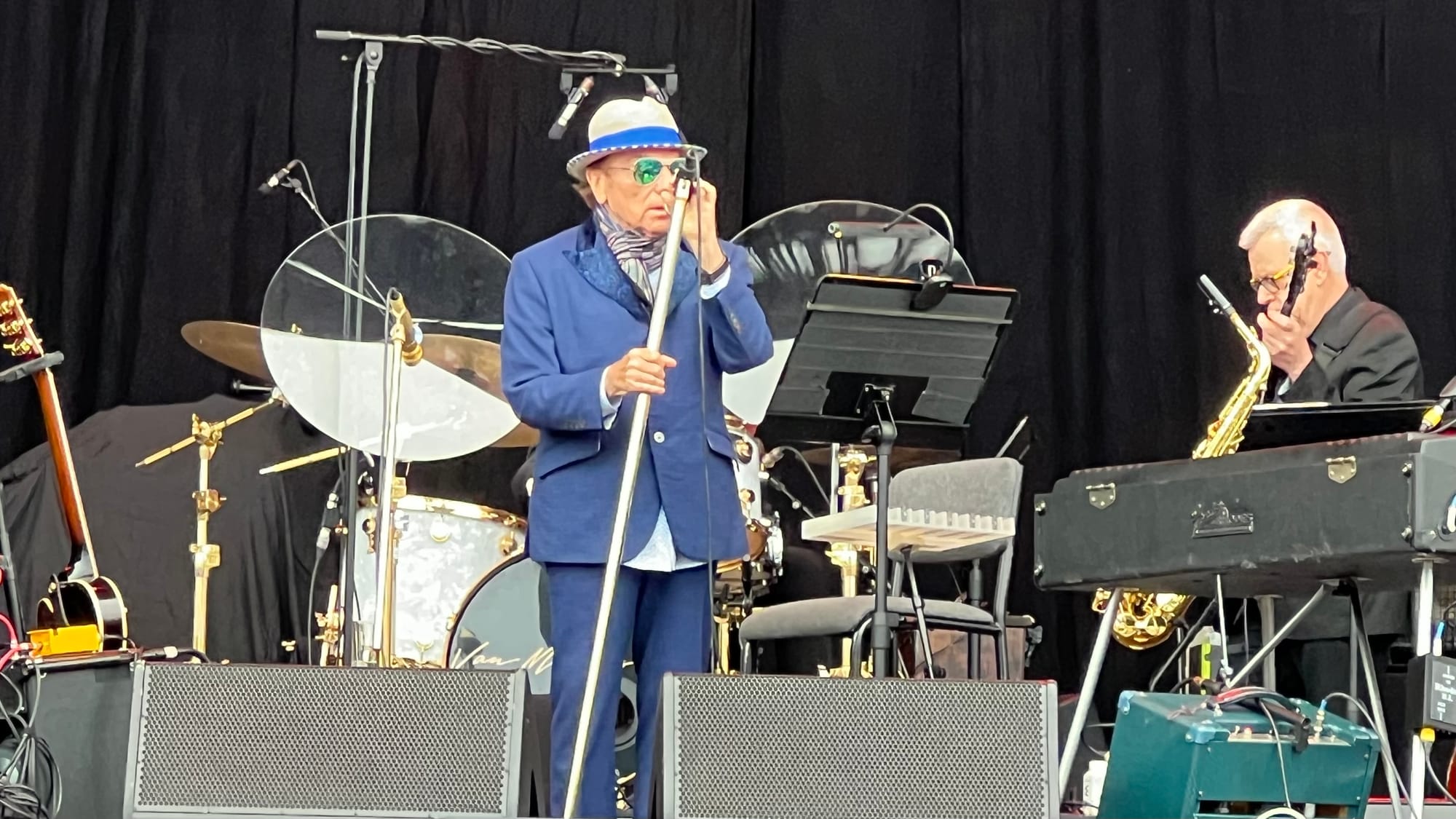

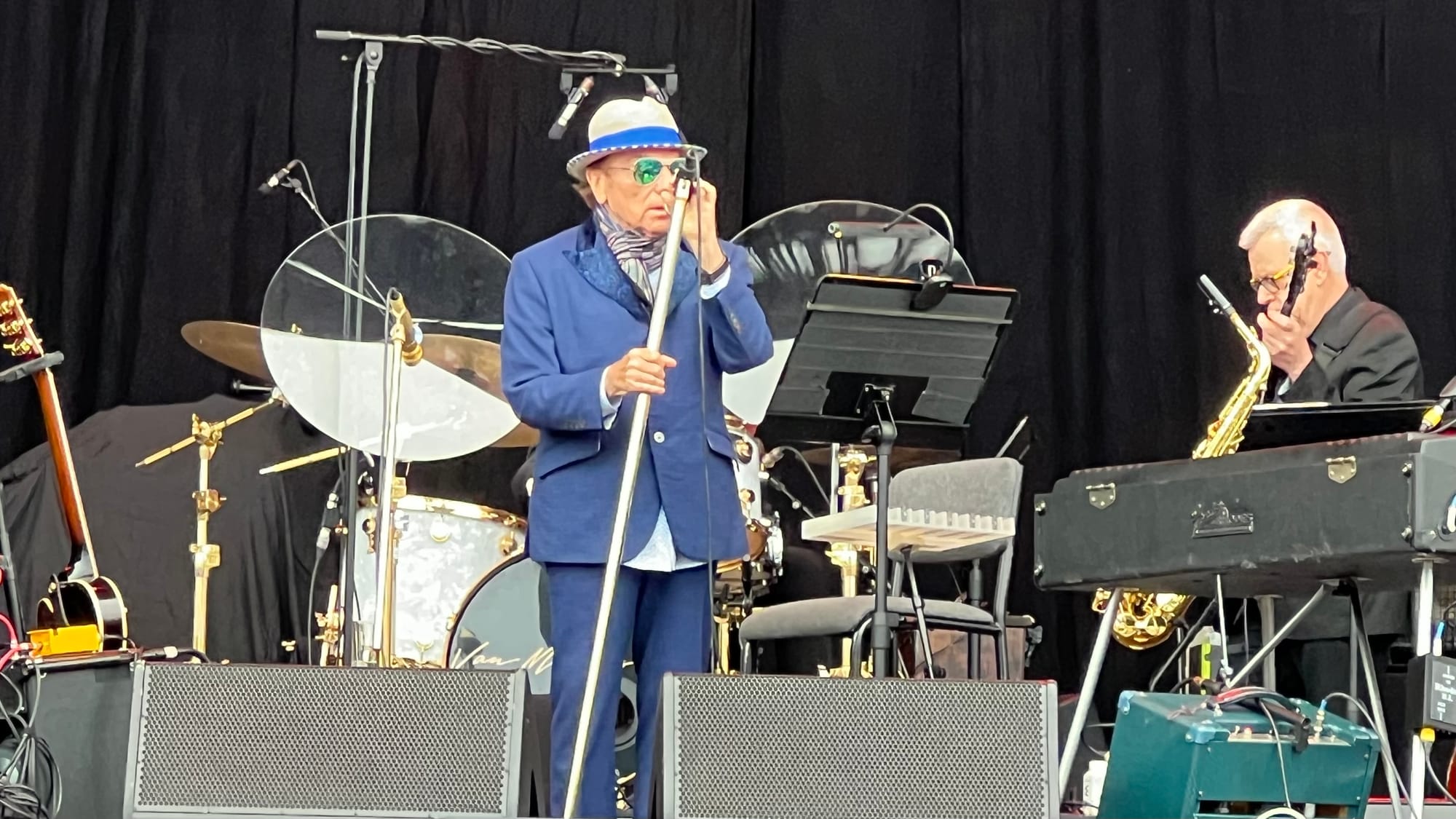

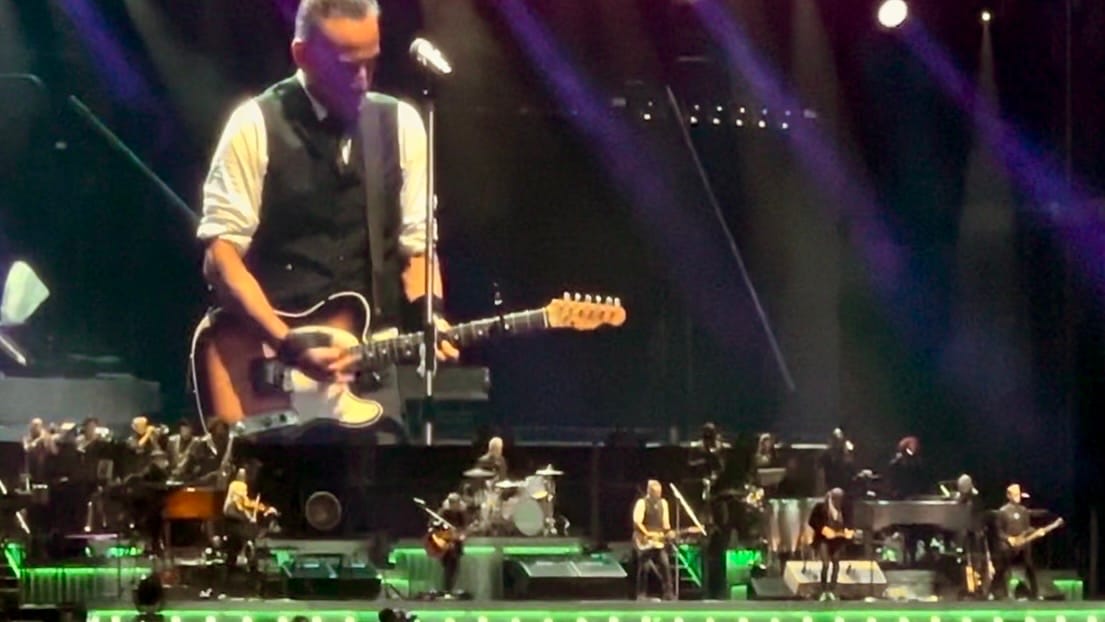

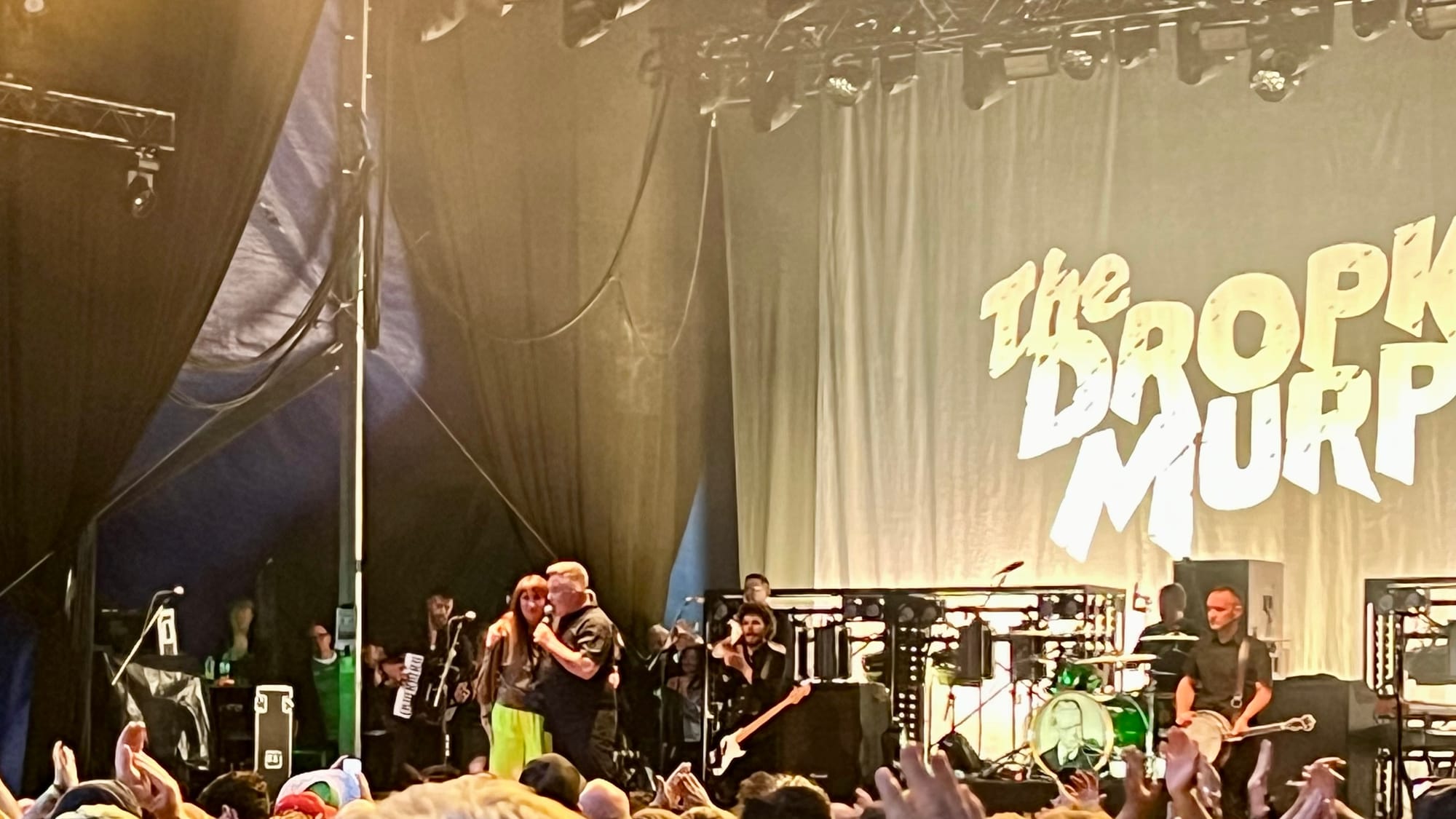

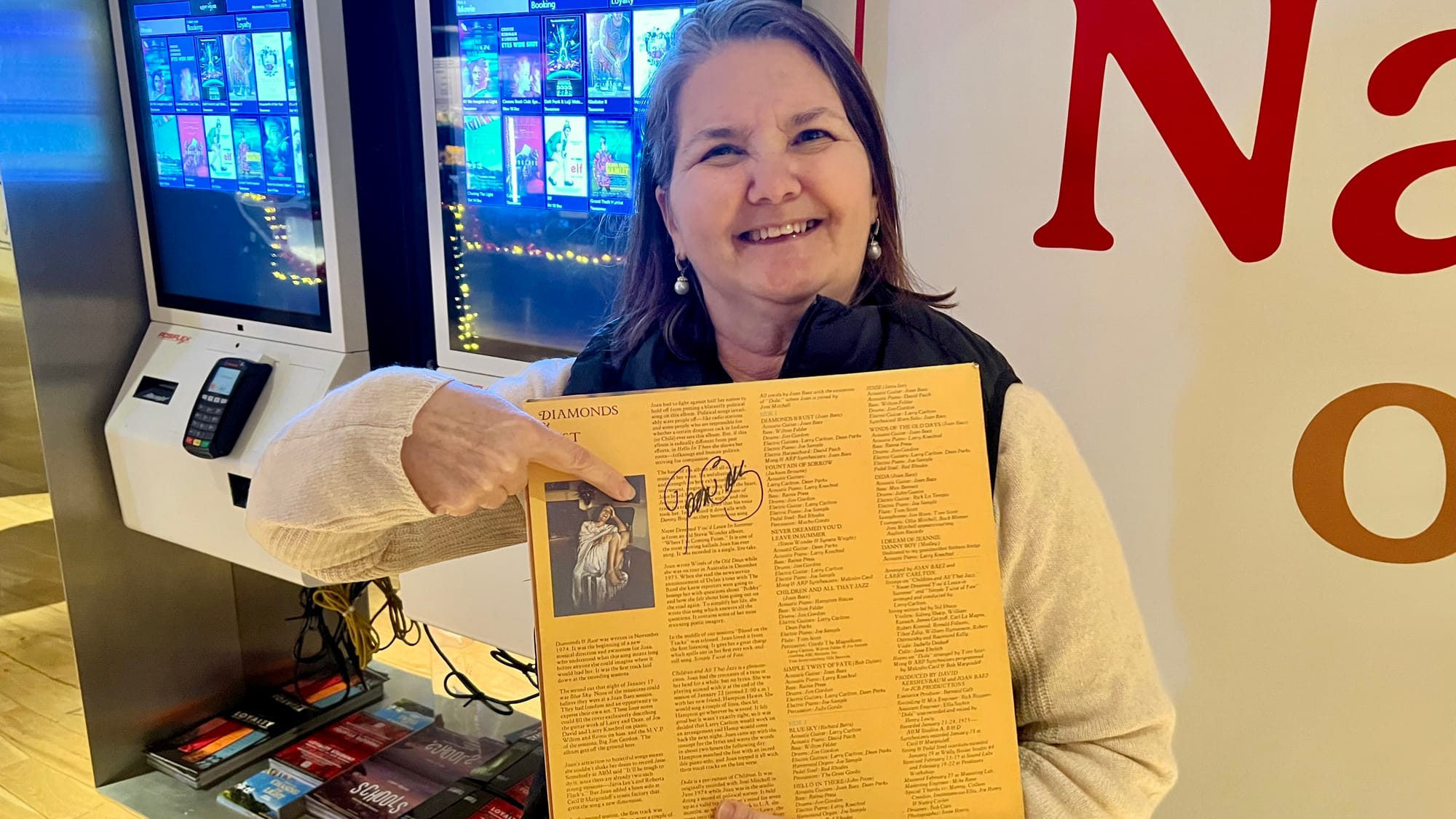

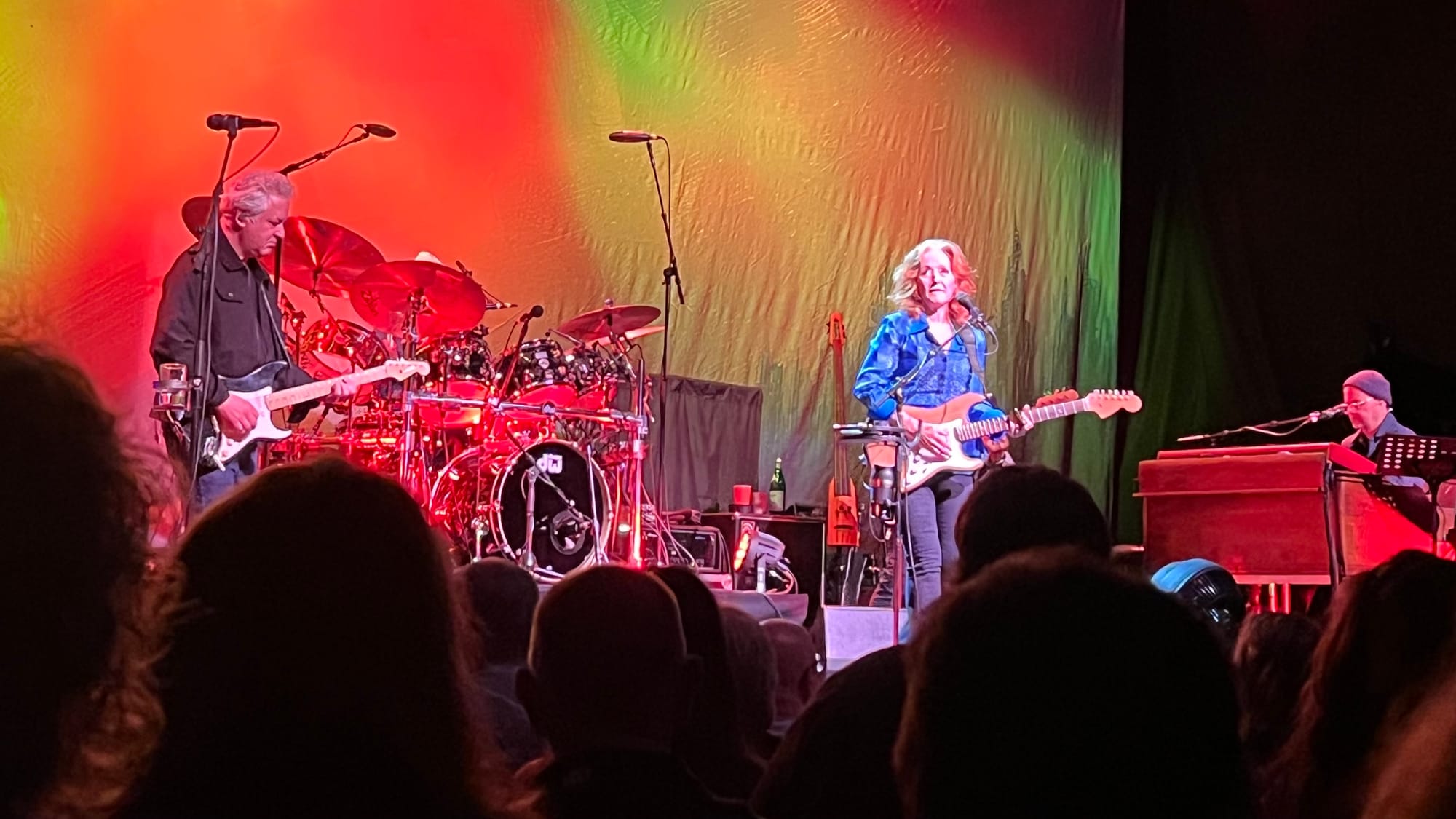

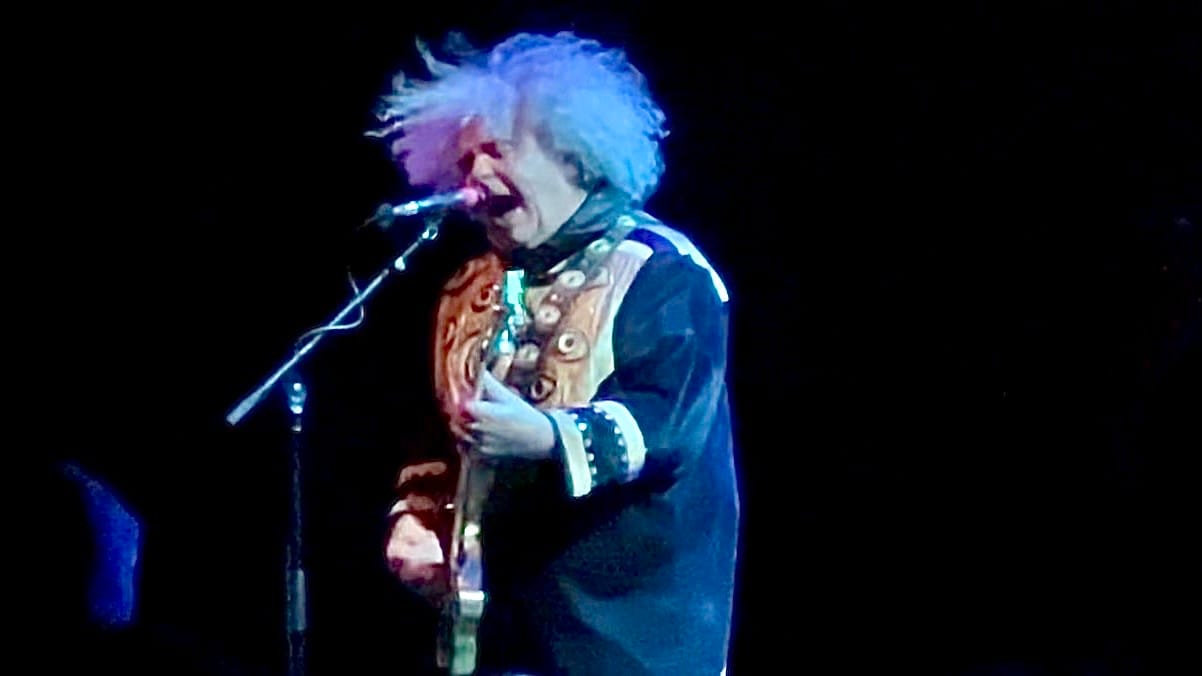

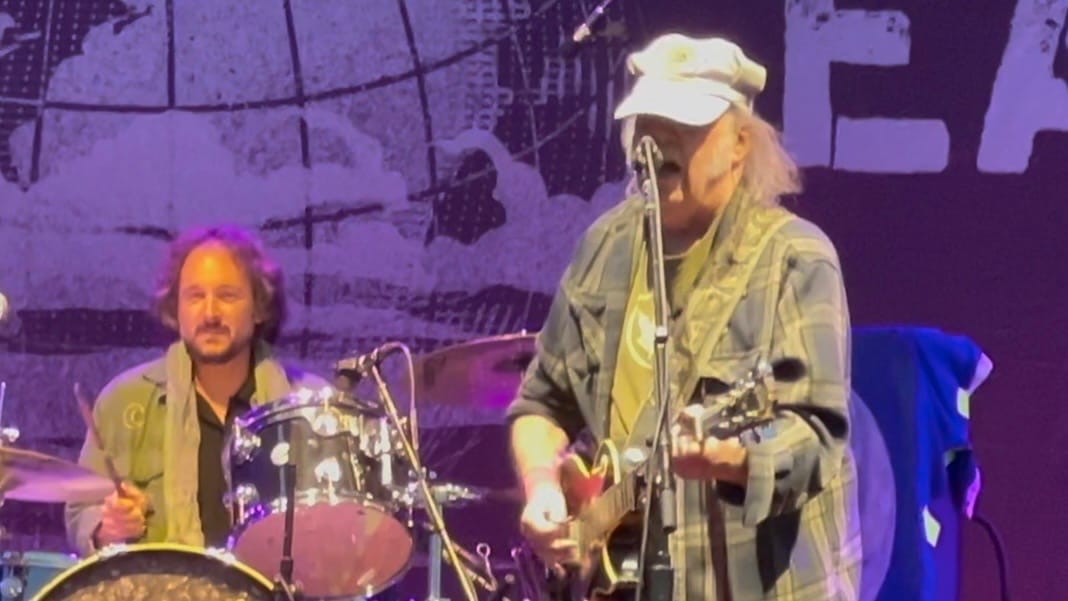

In Dublin alone, I’ve seen Glen Hansard, The Waterboys, Dropkick Murphys, Rhiannon Giddens, Russell Crowe (yes, that Russell Crowe), Colin Meloy of The Decemberists, Haircut 100, Rod Stewart, Eric Clapton, Joan Baez (documentary screening and Q&A), Lucinda Williams, Bonnie Raitt, Joe Jackson, Van Morrison, Pearl Jam, Bruce Springsteen, Elvis Costello, Bob Dylan and Neil Young.

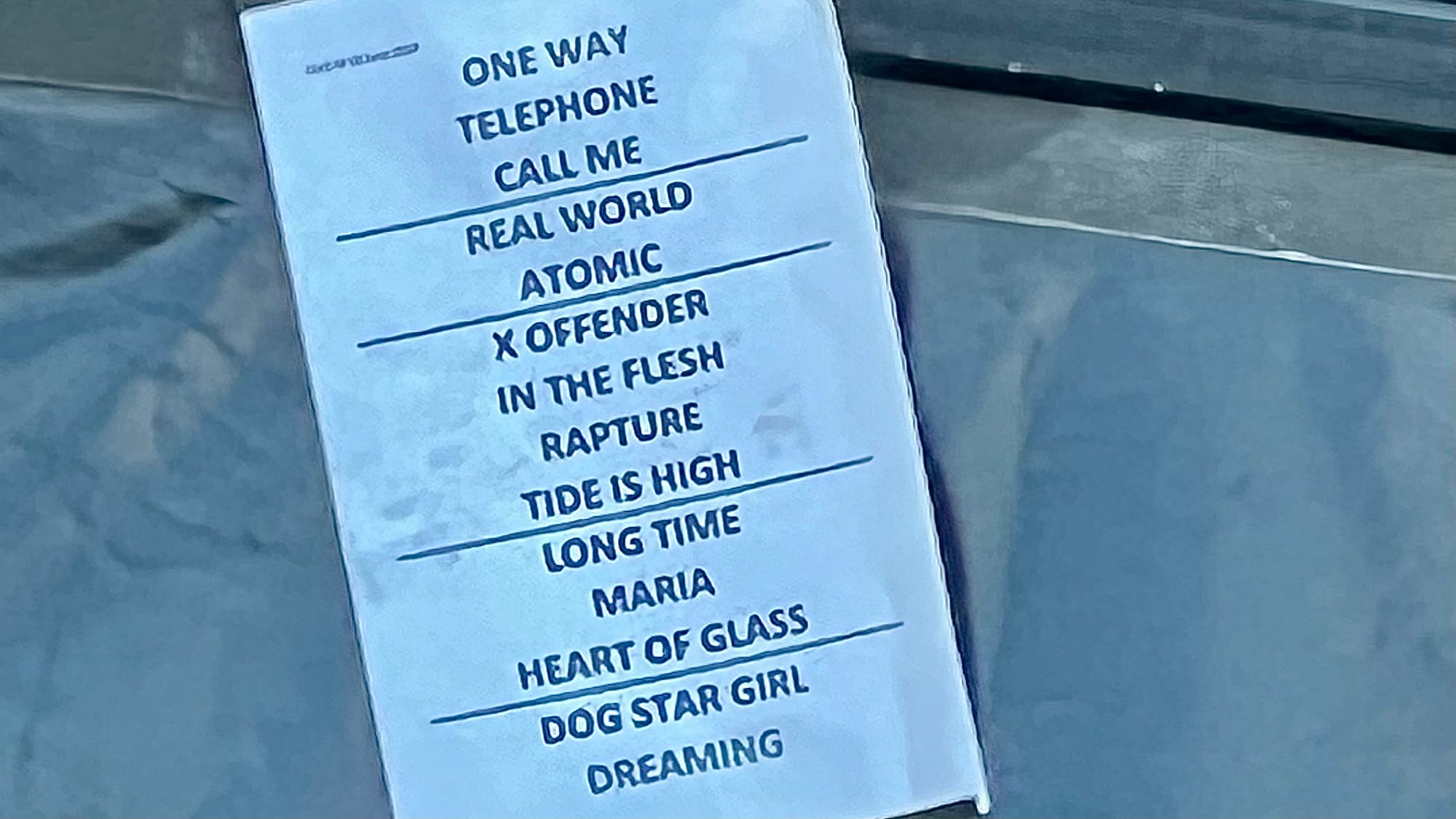

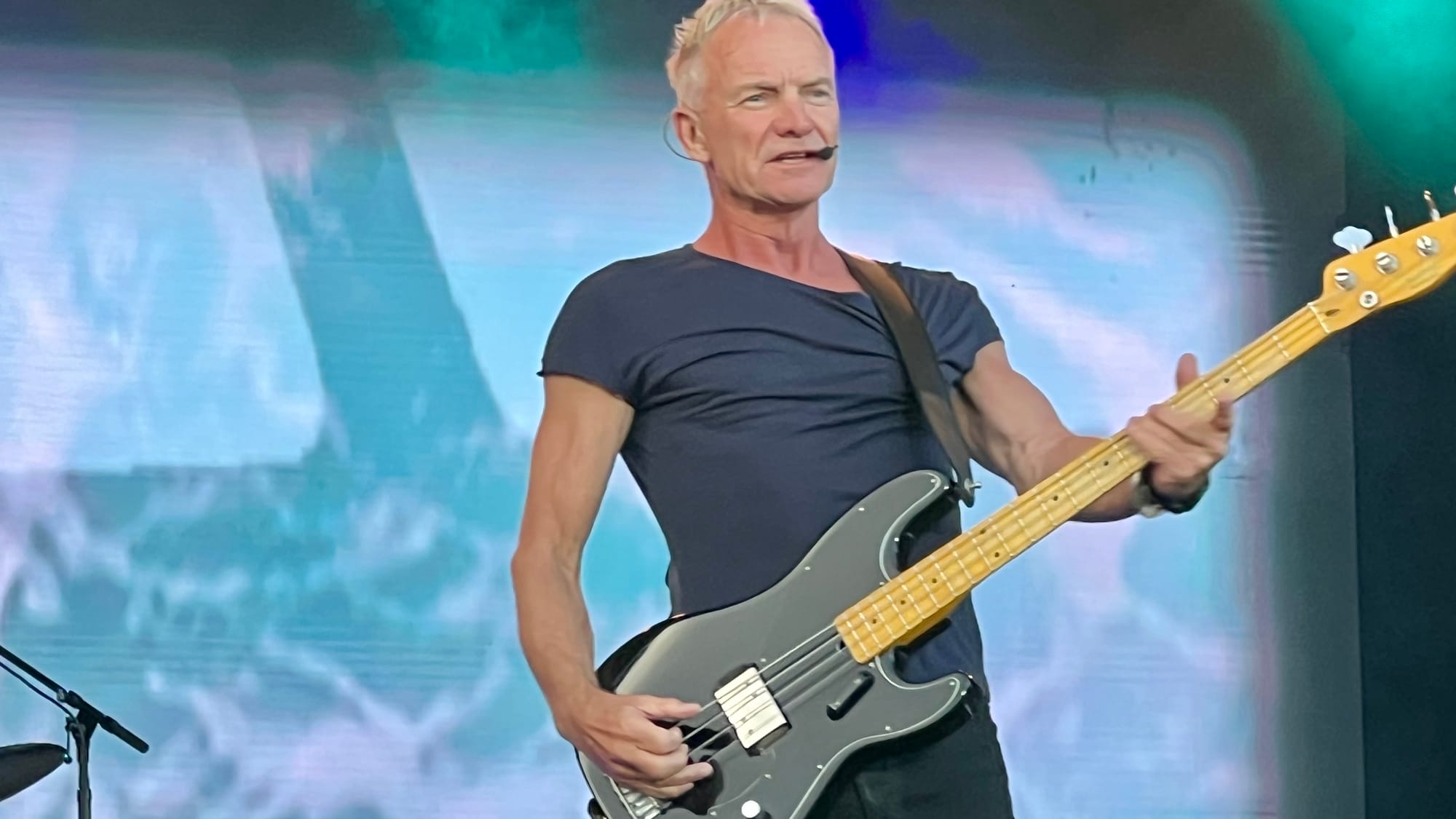

Outside Ireland, I saw Billy Joel at Principality Stadium in Cardiff, Wales. I traveled to Paris for Björk. I saw Sting in Cork with Blondie opening.

Soon, I’ll see Paul Simon and David Byrne — and possibly Garbage again (I have tickets this summer, though it conflicts with my work covering The Open at Royal Birkdale). I was scheduled to see Neil Young with Elvis Costello opening in Cork, but Neil just announced he will not be touring Europe this summer.

I’m still holding out hope that Death Cab for Cutie or Jack White will make it to Ireland.

Ticket prices have varied widely. Some were north of €100 for not-great seats. Others were €100 for “Gold Circle” access — a blocked-off area in front of the stage. Still others were closer to €50 for festival-style, general-admission shows.

That range got me thinking.

Why are these artists still touring?

Why are they still pressing vinyl?

Why do I sometimes buy a T-shirt — and occasionally add another LP to my shelf?

The answer isn’t nostalgia.

It’s durability.

Most of these artists built their audiences before streaming fragmented everything. They don’t rely on viral hits. They rely on loyalty. And loyalty has economic value.

A €100 Bob Dylan ticket signals cultural institution status. A €50 show at Vicar Street reflects a different scale, different overhead, different margins — but still a viable business. A Bruce Springsteen stadium date is a global event. A Glen Hansard performance feels intimate, but it sells steadily. Pearl Jam operates like a touring infrastructure. Van Morrison and Bonnie Raitt sit in the heritage lane. Colin Meloy’s solo performance carries the depth of The Decemberists’ catalog into a smaller room.

Different venues.

Different ticket prices.

Different production scales.

What changes from artist to artist is scale — not structure.

From a music business perspective, these performers don’t all occupy the same economic tier.

Springsteen, Dylan and Billy Joel operate at the level of global cultural institutions. Their catalogs are enormous assets. Touring reinforces brands that are already financially secure.

Pearl Jam runs more like a touring infrastructure — decades of fan loyalty, premium ticketing power and a built-in live ecosystem.

Van Morrison, Bonnie Raitt and Rod Stewart sit in the heritage model: deep catalogs, strong international demand and audiences willing to pay for legacy.

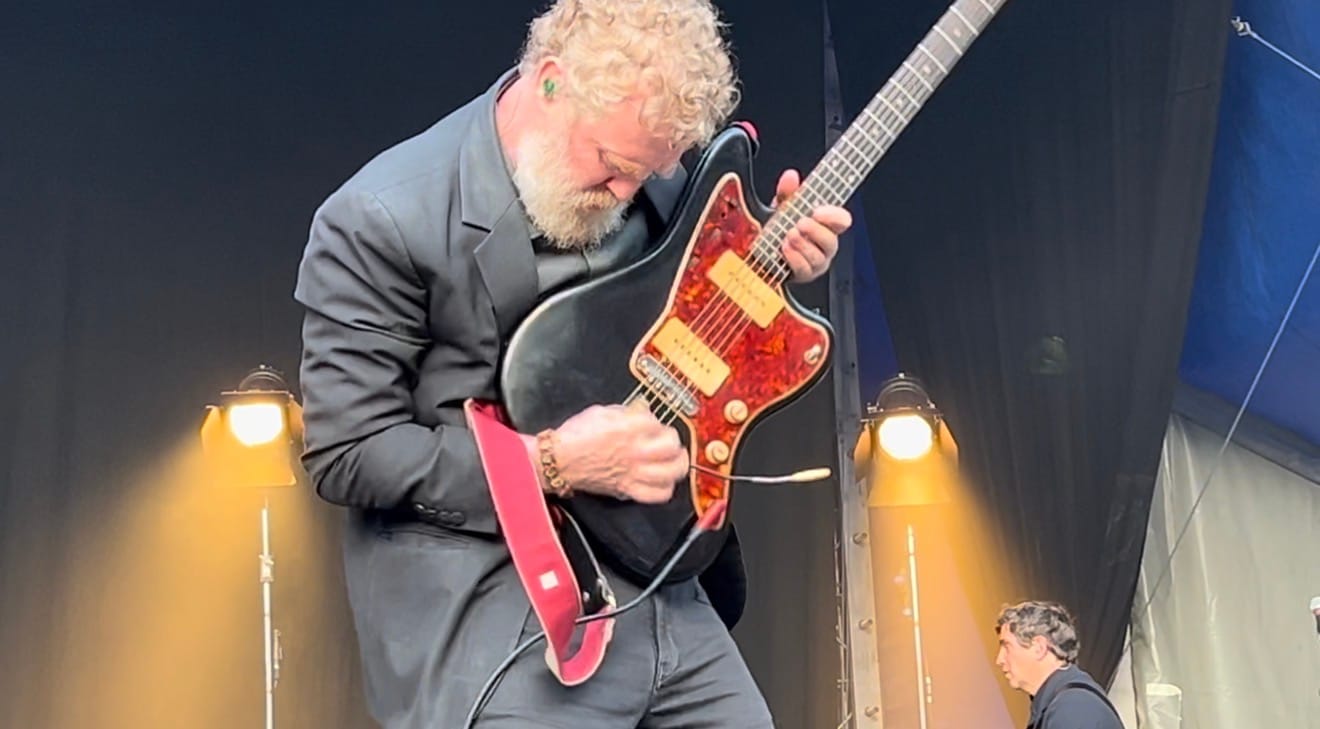

The Waterboys, Lucinda Williams and Dropkick Murphys represent durable touring businesses. They may not dominate streaming charts, but they command loyal live audiences year after year.

Artists like Glen Hansard and Colin Meloy occupy the prestige lane — smaller rooms, lower overhead, but highly engaged fans who buy records and show up consistently.

And then there are conceptual performers like Björk and David Byrne, whose live shows function almost as curated artistic productions — fewer dates, higher production value, premium positioning.

Different tiers.

Different economics.

Same durability.

Live performance is the engine.

Catalog is the safety net.

Merchandise is margin.

Vinyl is loyalty made physical.

When I buy a T-shirt, I’m participating in the touring economy. When I buy a vinyl record — especially a box set or special reissue — I’m contributing to the long-tail catalog value that keeps artists financially viable decades into their careers.

For some — Springsteen, Dylan, Billy Joel — touring is enormously lucrative and reinforces already massive catalogs. For others — The Waterboys, Lucinda Williams, Dropkick Murphys — touring is the core revenue driver. For Björk or David Byrne, live performance becomes conceptual architecture.

Moving countries reshaped my sense of time. Seeing artists who have been working for 30, 40, even 50 years — still drawing crowds at Dublin concerts and major venues across Ireland and Europe — made me think about endurance over hype.

These aren’t algorithm artists.

They’re institutions.

They’ve survived vinyl’s collapse, the CD boom, Napster, piracy, streaming and now the algorithm era. They tour because demand still exists. They release records because their audience still values ownership. They print shirts because fans still want something tangible.

I’m part of that economy now — an American in Ireland, standing in a crowd at Malahide Castle or the Olympia Theatre or Vicar Street (still my favorite venue), buying a shirt or a vinyl record, helping sustain a system built not on trends, but on trust.

Moving countries changed my address.

Standing in those crowds changed how I think about live music in Ireland — not as nostalgia, not as background noise, but as an ecosystem built on loyalty, scale and endurance.

In the streaming age, hype fades quickly.

Durability doesn’t.

Below is a sampling of the artists I’ve seen since moving to Ireland — from stadium-scale performances at Croke Park and Principality Stadium to intimate nights at Vicar Street and Whelan’s. The venues vary. The production budgets vary. The ticket prices certainly vary. But what ties them together is the same durable foundation: loyal audiences, deep catalogs and the continuing power of live performance.